“O, yes, I say it plain, America never was America to me,

And yet I swear this oath — America will be!”

– Langston Hughes

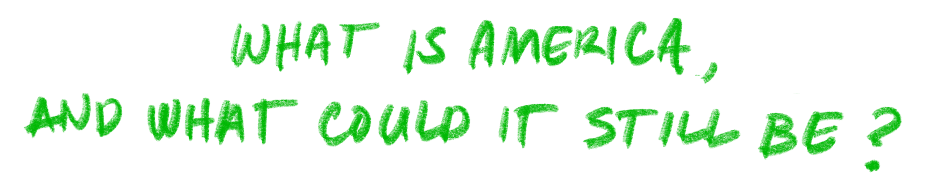

America will be – because we still believe in what America could be. On July 4, 2026, our nation will celebrate the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. It will be a time of celebration and remembrance. Most of all, it will be a time to ask, “What is America, and what could it still be?”

We cannot wait two years to begin answering that question, and answering it better than progressives have in a while. It is the central question of a third consecutive bitterly contested election. One particular and very ugly answer is on the rise:

"Let’s be blunt. The United States has become two nations occupying the same country. When pressed, or in private, many would now agree. Fewer are willing to take the next step and accept that most people living in the United States today—certainly more than half—are not Americans in any meaningful sense of the term… They do not believe in, live by, or even like the principles, traditions, and ideals that until recently defined America as a nation and as a people. It is not obvious what we should call these citizen-aliens, these non-American Americans; but they are something else."

That’s Glenn Ellmers of the MAGA-aligned Claremont Institute. He argues that the majority of people living in the United States are not Americans; and the real Americans are, he says, the ones who voted against Joe Biden in 2020.

Notions like this lay the groundwork for anti-democratic efforts. Trump advisor Stephen Miller is drawing up plans to “dramatically change the government’s interpretation of civil rights-era laws to focus on ‘anti-white racism’ rather than discrimination against people of color.” Fed by lies about the 2020 election, some states are making it harder to register to vote and cast a ballot. Led by former President Trump, majorities of Republicans deny the legitimacy of the 2020 vote, and GOP policymakers are increasingly publicly disdainful of democracy.

We are stuck in a sort of nasty feedback loop. The more Republicans dismiss democracy, the more Democrats are tempted to use defending democracy as a partisan cudgel. In turn, this makes pro-democratic efforts appear to be mere political posturing. Today 75 percent of Americans think democracy is at risk in the 2024 election, but for astonishingly different reasons.

In short: Some on the right are openly dismissive of democracy, or at least a democracy that includes black and brown voters, immigrant communities, even women. Too many of my fellows on the left are responding with open disdain for the right, labeling everyone who disagrees with them as inherently anti-democratic. The result? We are growing distant from each other and believe the worst about our neighbors. Our policymaking is gridlocked. The real threat to our democracy grows more urgent by the day.

More important than how we commemorate 250 years is what America will look like over the next 250 years. Our struggle over the meaning of America robs us of the common will to meet the deeper challenges that will define the next centuries. We cannot wait until 2026 to begin answering the fundamental question: “What is America, and what could it still be?”

I sit in an awkward position in all of this. I am a first-generation American, the proud daughter of immigrants from India. My family includes my Indian father and Mexican step-father, both of whom love and voted for President Trump. I walk around with brown skin and have raised brown children in an era of white nationalist politics. I am a proud progressive who was once an anarchist activist, yet paradoxically today I champion bipartisan solutions. I count as one of my greatest achievements being part of the team that passed criminal justice reform legislation, the First Step Act, by working with the Trump administration. Some alumni of that administration are now mobilizing against the democracy I love.

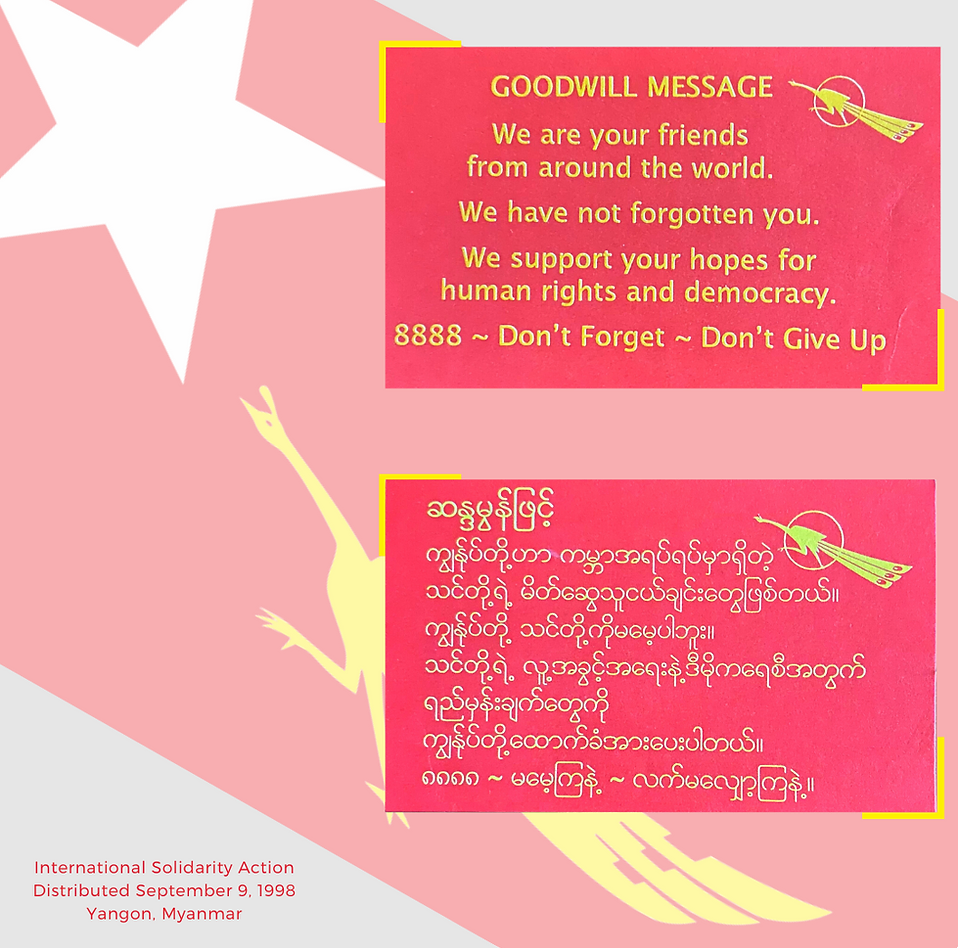

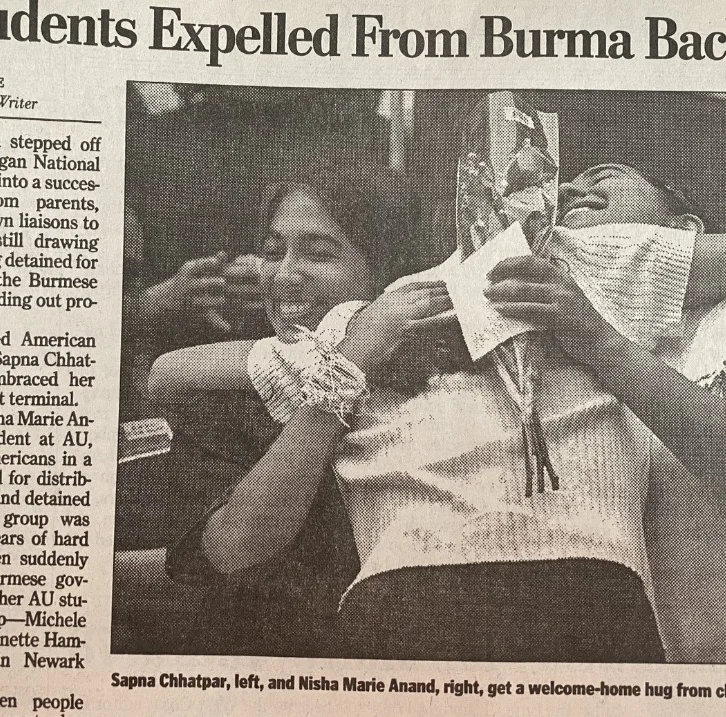

In 1998, I was sentenced to five years hard labor in Myanmar for handing out pro-democracy leaflets against the authoritarian military regime. I believed so much in democracy that I responded to the call of local leaders for outside help. After a week of imprisonment and after the sham trial and sentencing, I escaped through extraordinary diplomatic intervention. It was a GOP member of the House of Representatives, Chris Smith, who flew across the world to help. He believed, as I did, that democracy was not a left/right issue.

I always thought America, even with our imperfections, would be the beacon for countries like Myanmar. Yet today I look around and see my home country slipping in the wrong direction. I refuse to let that happen.

I cannot give up on the dream of America and still be my father’s daughter. Yet I would not be true to my friends, and my own community, if I slipped into a kind of cheap, bandwagon nationalism that ignores the things we have gotten wrong. So I have spent the last few years learning, listening, and trying to articulate a more joyful, boundless patriotism – one that says America’s best years are still ahead of us.

To really, truly love something, you have to love the reality of it, not just the idea of it. It is easy to fall in love with a superficial idea of a person – a version without faults, a version that lives in your head. Loving a real person, with all their flaws and imperfection, is far more difficult. But it is the only kind of true and lasting love. I have come to love America that way, and I want you to, as well.

"Nothin' really ends

For things to stay the same, they have to change again…

… I am the one to cleanse me of my Father's sins

American Requiem

– Beyonce

What is America, and what could it still be? It is a place of freedom – that began with millions in chains. A land of opportunity – rife with exploitation. An experiment in democracy – that excluded that majority. An expansive dream that stole land from indigenous communities. I could go on. America is as multifaceted and as capable of both grandeur and ugliness as the people who forged it. The complexity of America is not reflected in the limited patriotisms ascendant on both left and right.

A limited and angry patriotism has taken hold of my friends on the right. This limited patriotism says that America is defined only by its greatness. America’s best days are behind us, the story goes, and we need to get back to this idyllic state through some shift of culture or policy or even a deep remodeling of our newly inclusive democracy.

It is limited because it is only in love with one idea of America. It imagines a wonderful past, and conveniently ignores how difficult or downright awful that past was for people of color, women, lower-class workers, etc. It tells a half-story focused on America’s greatness, and shoves its fingers in its ears and hums when anyone tries to address our real history.

It is angry because it imagines that this America has somehow been stolen or degraded. Political and media figures deliberately stoke this anger and chain it to a particular vision of scaling back democracy and undermining steps toward equity for women and communities of color. This limited, angry patriotism is now a potent threat aiming to produce a limited, angry democracy.

A limited and sad patriotism has taken hold of my friends on the left. It is limited because it loves only the idea of what America could be. It is sad because it sees only the worst in America. It will love America fully only in some future where it becomes what we want it to be, when its reality finally matches up with our vision of a just society. Instead of angry, it is gloomy and dispiriting, seemingly unable to conjure the hopefulness that we need to meet the challenges of the moment. It tells a half-story, too: of mere oppression and injustice.

This limited and sad patriotism is, to me, more depressing than threatening. I know my friends on the right do not see it this way. They see it as a wholesale rewriting of American values and history – rather than a corrective that includes more voices – that is linked to a fundamental effort to change the American electorate. To me, this view flirts with great replacement conspiracies and leaves out people of color who have been part of America from the beginning. Limited and angry patriotism is a road to white nationalism, while limited and sad patriotism is a path to apathy and stagnation. We cannot pretend they are equally bad.

Unfortunately, the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence is poised to be a depressing battle between these two half-stories. Nowhere between the battle lines will we hear the whole of the ugliness and beauty of this dream called America. Such a battle will make us all madder at each other, and get us nowhere in the process.

If a fruitless battle is the most likely scenario, a celebration of cheap unity is the second. What do I mean by cheap unity? Almost all of us seek a sense of belonging and community in our lives, workplaces, and nation. Unfortunately, we usually want it on our terms. Instead of battling it out, we settle for thin platitudes and turning a blind eye to real differences.

Cheap unity makes people feel comfortable, but also that they have to hide their full truth. In our political life, cheap unity emerges as elite self-congratulations and a kind of top-down bipartisanship that helps the rich and well-connected at the expense of the down-and-out. It substitutes jingoism for truth-telling, and stereotypes of what it means to be American for the more complicated reality.

The alternative has always been what I call fierce unity. Fierce unity does not ignore difference. It is not uniformity or elite bipartisanship. It is everyday people risking being uncomfortable by finding common ground with people who disagree with you on everything. It means starting with the people who are hurting the most, even if they are not on our side politically – and then looking for unlikely allies and commonsense solutions to actually make things better.

Unfortunately, we are bound to encounter a lot more cheap unity than fierce unity around the 250th anniversary. It will be well-funded, come with a list of elite endorsements a mile long, and traffic in buzzwords without substance. And it will have all the spontaneous joy of an extended family trying to force its way through Thanksgiving without a fight.

“The world is to be moved one generation forward – whether by us, by blind force, by fate, or by God!

If thou believest, all things are possible; and as thou believest, so be it unto thee.”

– Anna Julia Cooper

Neither cheap unity nor a half-story of America can meet the moment. I do not have all the answers for what the 250th should look like. But I can suggest some principles that will put us on the right track.

First, we need to embrace a boundless patriotism that tells the full story of America. Second, we need to risk being uncomfortable to solve problems instead of luxuriating in our siloes. Third, our celebration must have at its center a spirit of revival that mixes joy with confession. Fourth, threaded throughout must be an effort to get us talking to each other again.

What is America? The alternative to limited patriotism is boundless patriotism. It is patriotic because it believes there is a core dream in America that has been beautiful and inspiring from the start. It shares the faith of the freedom fighters who have gone before us. Boundless patriotism says that we cannot give up on America without giving up on abolitionists, suffragists, labor activists, civil rights marchers, and yes, even those imperfect people who dreamed big and wrote the Declaration of Independence.

It is boundless because it still believes that America’s best days lay ahead of us, not in our past. We should always be expanding the boundaries of who belongs, who counts, and what freedom, justice and equality look like in a new century. When we honor America, we honor our elders – including the ones who fought to give us a better America.

America is like a grand old tree. Yes, it will always be rooted in deep trauma and injustice. But from the start it has been reaching for the sky, and it never stops growing. It sprouts new branches, it grows new rings. You can see in it the scars of the past, of broken branches and cold winters and wildfires. Initials carved into its bark will not fade quickly. It will go through seasons of growth and seasons of falling leaves. Yet there are always buds and new branches reaching outward.

America must always, to use Cooper’s words, “be moved one generation forward.” Every generation is called not merely to celebrate the founders, but to join them. We must become new founders – refounding America with each generation. We cannot abandon our founding principles, or overlook our failure to live up to them. We need to love America so boundlessly that we are willing to listen to those who say, with Hughes, “America never was America for me,” – while refounding the nation so that America will be.

What will America be? We face massive challenges, including the climate crisis, economic inequality and lack of opportunity, rapidly shifting technology, and the continuing legacies of exclusion and racism. Any of these could doom the American experiment in the next century. In fact, the crushing weight of these challenges and the transitions involved are leaving Americans feeling more economically precarious and socially unmoored than they have in years, feeding the worst instincts in our body politic.

We cannot move America one generation forward without addressing these urgent challenges. We cannot bridge our divides without taking concrete steps on real problems. In the absence of progress that makes people’s lives better, all our efforts at bridgebuilding and dialogue will crumble under the weight of bitter envy and accusation.

Yet I believe there is a way to make progress on our core challenges – and do so in a way that not only reckons with our history and our future, but also brings us together instead of worsening division.

For instance, If we are going to truly reckon with America’s history, we need to deal with mass incarceration. Slavery – along with violence against native communities and the denial of suffrage to women – was core to America’s original sin. Slavery became Jim Crow which became, in turn, the “New Jim Crow” of mass incarceration. We can deal with the ugly parts of our legacy by confronting how they continue today. That means disrupting a broken criminal justice system, closing prisons, and investing in solutions that actually work.

If we are going to truly deal with America as it is right now, we need to realize we are in the midst of a massive shift from dirty to clean energy. Green investments are needed in order to mitigate the worst of the climate crisis, as well as to position our nation for a future that will be (whether we like it or not!) one of wind and sun instead of mountaintop removal and offshore drilling. America will not be strong in the future if all the green jobs are overseas. America will not be united if the people dealing with the worst of pollution pain never share in green wealth. We must build an economy that is not just green for some, but green for all. We cannot give up on terms like equity, or give into smear campaigns against the very notion.

If we are going to truly build for America’s future, we need to address rising inequality, diminishing opportunity, and the way technology is complicating both. The jobs of the future are increasingly high-tech, and artificial intelligence is a still-unknown variable. Yet we know that the technology industry today remains disproportionately white, male, educated, and upper middle class. If you grow up in a small rural town or in a depressed big city block, it can seem like these jobs are out of reach. We are failing to tap the real wisdom, creativity, and brilliance of the full American people. As a result, technology is poised to exacerbate income and wealth inequality, instead of mitigating it. Without doors of opportunity to the high-tech industries of the future, America will stagnate, and Americans will turn on each other ever more.

The good news is that it is possible to build common ground on these three fronts. I have seen libertarians team up with formerly incarcerated individuals to build a system that spends less money and locks up fewer people. Conservatives who value American energy are working for a better climate future with environmentalists worried about smokestack pollution. Big-name companies who know they are missing out on talent are partnering up to build a pipeline into tech from black and brown communities.

We can answer the questions, “What is America, and what could it still be?” by actually tackling problems. We can do so in a way that brings us closer together instead of dividing us. In the process, we can use the 250th anniversary to make America more free in the future than we are today.

What is America, and what will it be? What we need in 2026 is more akin to a revival. Joy, celebration, the fervent hope for a tomorrow unbounded by our past? Yes, absolutely. It must somehow be commingled with a confession of what we have gotten wrong. In fact, it will only be truly joyful if it flows from this place of confession. It is only by admitting the full reality of America that we can love it truly. Only by holding the American dream and American shortcomings in tension can we joyfully look to the future. If you deny that America has never been flawed you will never learn; if you see only failures, you will never hope for better. Only by looking at how we have overcome our own failings can we face the future inspired to do so again.

Study after study says that we are less polarized than we think. We assume that the people who disagree with us are all radicals with utterly different worldviews, when the data says otherwise. Liberals and conservatives are all a lot more moderate in their actual views than in what we think of each other. Therein lies our hope. If we start out with the assumption that we can work together to build a better America, our belief can become reality. If we pick concrete, commonsense projects that will make our communities better, and start working together on them, we can begin to mend the frayed edges of our social fabric.

We must make the 250th anniversary a call to action. It should inspire us to tell the full story of America in a way that gives us hope for the future. It should also demand that we come together, find common ground, and refound America for the next generation to inherit. Anything less, and the nation we love could slip away.